Landscape and Geology of the Shepton Mallet area.

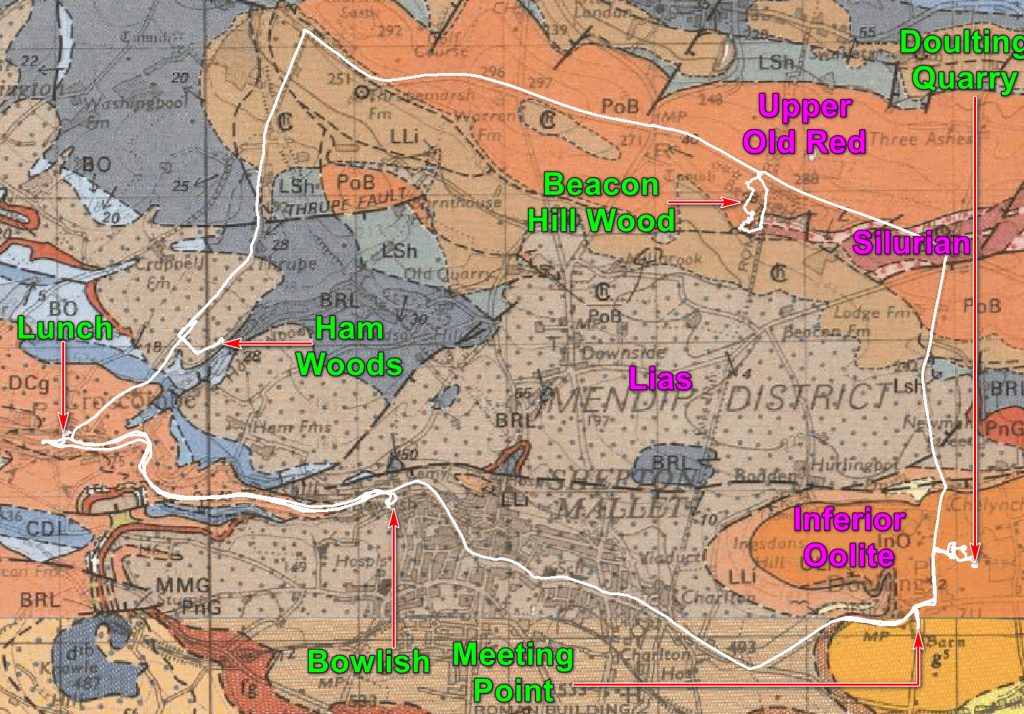

On Wednesday 22nd April 2015 a group of us toured the countryside near Shepton Mallet to look at Late Triassic and Jurassic rocks of the area. And also to look at the Doulting Rock Quarries. We were from various geological groups in the South West and were led by Dr. Doug Robinson, lately of Bristol University.

Outline of Geology

The Late Triassic and Jurassic rocks exposed in the area around Shepton Mallet represent the gradual transgression onto the land by the sea beginning at the end of the Triassic, and eventually transforming the Mendip landscape into an archipelago. Along the shoreline of this archipelago the shell-rich conglomeratic limestones of the Downside Stone and Chilcote Stone were formed. In slightly deeper, quieter conditions as near Bowlish, the thin, alternations of limestone and mudstone, more typical of the Lias were deposited. Further rise in sea level in the Mid Jurassic resulted in the cutting of a spectacular planar erosion surface across the folded sequences of the Mendip hills. Above this surface the Inferior Oolite, shallow water limestones were deposited and capped by clay-rich sediments of the Fuller’s Earth Formation.

Inferior Oolite – is a yellow-weathering, limestone of the Middle Jurassic. The limestone is richly fossiliferous with brachiopods, bivalves, ammonites and echinoids. The sequence contains oolitic horizons representative of shallow high-energy marine environments. There is often evidence of breaks in sedimentation, as shown by eroded, bored or oyster-covered surfaces, as well as conglomeratic horizons. The best known rock in this area is from the Doulting quarries which has been quarried as a building material, especially for Glastonbury Abbey and Wells Cathedral.

Lias Group – the Charmouth Mudstone formation is the youngest of the Lias Group, but much of the succession is missing, and what is present is poorly exposed. Between Shepton Mallet and Wells, the usual interbedded succession of mudstone and thin limestone of the Lias is replaced entirely by conglomeratic limestone known as Downside Stone and Chilcote Stone. This is an ancient shoreline deposit formed around the Mendip archipelago. There are beds of broken, thickshelled bivalves, with Carboniferous limestone clasts indicating continued erosion of the Mendips. The Downside stone is exposed at Bowlish where it forms interbedded grey limestones and mudstones indicating a change in deposition from a nearshore to a deeper (but remaining relatively shallow) offshore. Ammonites, gastropods, bivalves and coral, have been reported along some wood fragments indicating the proximity of land.

The Lias Group more typically forms regularly interbedded thin limestones and dark mudstones, and are richly fossiliferous, with ammonites and bivalves. They were deposited in open-water, some distance from landmasses, and so are not represented near Shepton.

Silurian and Devonian – North of Croscombe and Shepton is the EW trending Beacon Hill, the easternmost of four periclines forming the core of the Mendip Hills.

The oldest rocks in the Mendips are exposed in the core of this pericline – the Silurian, Coalbrookdale Formation. It is a sequence of mudstones overlain by tuffs, agglomerates and andesitic lava flows – one of the few places in the UK where Silurian volcanics are exposed.

The immediate envelope to the Silurian core is formed of Devonian rocks of the Portishead Formation, representative of a fluviatile system in an arid, continental environment at the southern margin the Caledonian mountains. The rocks are dominantly red sandstone, with some purplish shales and mudstones.

The Excursion

The group assembled in the village of Doulting, at the tithe barn. Doulting dates from the 8th century when King Ine of Wessex gave the estate to Glastonbury Abbey after his nephew St Aldhem died in the village in 709. In his honour the local spring, the source of the River Sheppey is called St Aldhelm’s Well. The spring occurs where water percolating through the permeable Inferior Oolite meets the underlying impermeable Charmouth Mudstone.

Doulting Manor was a grange of Glastonbury Abbey. The Tithe barn built in 15C is one of four surviving barns belonging to that abbey The barn has the same fine ashlar stone walls and raisedcruck roof as the other barns. A significant difference is that it has two large wagon porches facing the manor farmhouse, which was built in C17. It is eight bays long, one bay longer than Glastonbury Abbey Barn and Pilton Tithe Barn.

After this taste of recent history we drove to the Doulting Stone Quarries which record more ancient events.

The Doulting Quarries were used by the Romans as shown the use of Doulting stone cut quoins in the remains of a building in Shepton Mallet, next to Fosse Lane. The quarry became important in Medieval times with the building of Glastonbury Abbey, and it was in possession of the Abbey from the 8th or 9th century. This makes it one of the oldest and longest worked quarries in the UK. The Abbey’s tight control limited use of the stone to largely ecclesiastical buildings, with even the Dean and Chapter of Wells Cathedral having difficulty in obtaining supplies. This constraint meant that the local Chilcote stone (over which the Dean did have control), was initially more widely used around Wells. Each subsequent stone extraction episode was subject to a new arrangement, such as in 1354 when Walter de Monyngton (Abbot of Glastonbury) granted William de Camel, Canon of Wells, 40 wainloads of freestone for the new cloister house and 20 loads for other works. The cost of haulage to Wells in the 1400s was 12d (a shilling) (5p) per load. Records in 1381 specifically refer to Chelynch Quarry (which operated for six centuries, closing in 1967). The quarry was in fact a patchwork of operations from Chelynch in the north to the present site in Doulting.

About 10 colleges and some public buildings in Oxford were built of Doulting stone in the 1870s. It was also used for the interior of the Guildford Cathedral in the 1930s. The quarry was closed in the 1970s, but reopened for a major restoration programme at Wells Cathedral, and for housing developments in Shepton Mallet, and in restoration and new work at Bury St Edmunds Cathedral.

The control of the quarries over the last 150 years has been chequered and at times complicated. Various people were employed by the Strode family, as the landowners, to manage operations until they were leased to Charles Trask and Sons in 1889, a company then operating Ham Hill quarries near Yeovil. Eventually the group became part of the Bath and Portland Group in the 1930s, which was acquired by ARC Ltd. in 1985. When the lease expired in 1993/4, Mr Keevil took on operations directly as Doulting Stone and continues today with 200,000 tons of reserve.

And Mr Keevil proved to be a very knowledgeable and welcoming host as he showed us round his quarry and workshops, telling us how to choose a good bit of rock for further value enhancement – beware the shakes and other faults and joints! Although bedding is difficult to see in Doulting Stone, it is there and has a considerable affect on the rocks strength. The rock is strong when forces are at right angles to the bedding, considerably less so when it is not. We learnt this and much more as we were shown round.

Doulting stone is light brown in contrast to Bathstone and is also not a true oolite. Much of the material is finely wave-broken crinoid debris, perhaps derived from the adjacent Carboniferous Limestone, and then recrystallised as a new rock. Ooliths are uncommon in many blocks.

From the quarry we should have gone to look at the Downside facies at Bowlish but we had spent so long at Doulting that we went straight to lunch at the George Inn at Croscombe, followed by a post-prandial tour of the Church of St Mary the Virgin, built of the local Chilcote (or is it Downside?) Stone.

These three rocks – Doulting, Chilcote and Downside are the rocks we concentrated on; they are relatively close together but each is distinct.

Doulting Stone is a bit younger than the others and was laid down in Inferior Oolite (Early Jurassic) times, but is not particularly oolitic. It was laid down in a high energy shoreline environment which ground down most fossils. And then diagenesis led to calcite recrystallisation.

Chilcote and Downside Stone are of the same age and seem to have interchangeable names. In the Geological Survey’s publication “A walkers’ guide to the geology and landscapes of the eastern Mendip” this is so, although there are two different rock types covered by the terms. I thought that the Chilcote Stone – often talked of as a poor man’s Doulting Stone – is a near shore, high energy, deposit of Blue Lias/Charmouth Mudstone age (i.e. at the junction of Triasic and Jurassic time). It is a white, coarsely crystalline, shelly and sandy limestone. We saw it in an abandoned quarry in Ham Woods. The Survey guide assures us that this is Downside Stone. But they also call the rock found in the road cutting in Bowlish as Downside although it is a fine grained Liassic type limestone. It may have been fairly close to the shore but it is a deposit of deeper, tranquil waters. It is certainly deep waters for the non-specialist!

After our look at the rocks in the valley we headed up hill to Beacon Hill, one of the four periclines of the Mendips. A pericline is an anticline with aspirations to be a dome. This one has a core of Silurian volcanics and is surrounded by Old Red Sandstone. We parked at Beacon Hill Wood.

Beacon Wood probably lost its original woodland cover in the Neolithic, 5-6000 years ago, and in the Bronze Age, – 4000 years ago it was open downland. At least 12 round barrows line the ridge in the wood, but some are in the field to the west. The barrows had cremated human remains and funerary pottery of the early 2nd millennium BC. Later, in the Iron Age, the Devonian pebbly sandstone forming the hill was quarried to make querns and millstones, used in local settlements such as the Glastonbury Lake Villages or South Cadbury Castle. The Devonian sandstone and Silurian volcanic rocks were also utilised as a source of grit tempering for the distinctive Iron Age pottery of Glastonbury.

Two main Roman roads – the Fosse Way and a road from the Mendip lead mines to Southampton – intersected on the hill top, although little remains today. There was a Roman expansion in the rakes, quarry pits and working platforms in the wood, with querns and millstones produced here being been found at settlements in Ilchester, Shepton Mallet and Camerton.

From the edge of the wood we could look southwards and imagine a Jurassic sea advancing over an Old Red Sandstone island. And in the core of the island we could see the harder sandstone forming steep slopes around the softer volcanics.

And then we went home! But only after expressing our thanks to Doug Robinson for arranging everything for a very good excursion – rocks, quarries and especially the weather!